I was twenty-two then, living in a bedsit with three men I didn’t know. Each man had bad habits; badges of football teams tattooed to limbs like biker patches on denim jackets. They shared little patience for small talk. Had little room in their dialogue for talk beyond a current grievance. The men liked to play songs by the band Oasis loudly in their rooms before nights out or in. After a while, music began to sound like screeching tires, I don’t know why.

Each man worked with their hands by day. In the bathroom I would see bottles of O’Keefe's working man's gel, placed on a glass shelf stained by spit and toothpaste, covered in brittle hair cut from shaving. Rare signs of self-care from men coming up or down daily. By night they drank hard: beer, vodka, gin. Sat around a kitchen table covered in ash and empty bottles, beneath a dense plume of smoke, they shared an almost meditative silence in one another’s presence. Until drunk or high. Then it all came out:

She’s told me I need to pay this much for the boys school clothes.

My boss is a right twat.

A mate owes me money, needs to pay up.

In three months, I never ate in the kitchen, a lone communal space where a thousand words were left unspoken about how broken lives had become. When the men did communicate, inebriation made them nightclub loud. Conversations of the past: a pub fight, football match, ex-girl with a child they’re not allowed to see anymore unsupervised. Noise bellowed from the kitchen like pain. Sometimes they would play cards for money. I chose to leave the house on these nights. The men I lived among only seemed free when in a state of—could not give a shit.

*

The room I rented at the bedsit had its own lock and key. I said I’d take it over the phone once this had been confirmed to me by the landlord. Then I packed and lugged my things onto public transport: books, clothes, photo albums, a typewriter named Bluebird that came with its own carry case.

I had found my new accommodation on Craigslist. The ad read: room for rent. pay cash weekly. I remember thinking, ‘this landlord probably reads Hemingway,’ or maybe I thought, ‘the website charges by the word for ads.’ Anyway, on induction at the bedsit there would be no contract to sign or notice period required. My landlord was a large, thick-boned woman with flaming red hair, skull and bone tattoos. She had the impatience of someone who had dealt with too many lost men in her life already. We shared few words, there were no inquisitions relating to identification, where I was from or how long I’d be staying.

‘Everyone shares the bathroom and kitchen,’ she said. ‘The rooms have locks. I’d use yours if I were you, this lot can be lively.’

‘No problem.’

‘Why would it be a problem?’

‘It wouldn’t.’

‘It’s sixty a week, cash. I don’t want to have to come looking for you.’

‘I understand.’

‘Last one who took the room didn’t.’

Silence filled our space like mustard gas. I followed as she showed me around a tiny bedroom, pulling on a smoke like she was sucking on a straw. The space contained a bed, lightbulb, shelves. I was on the ground floor. The bedroom faced a busy main road famous for daylight muggings. I said the place was fine, paid sixty pounds cash for the week ahead, and accepted two keys. On departure, my new landlord paused at the front door.

‘Don’t be late with the money,’ she said.

I nodded, entered the bedroom with a backpack and slung in on a springless mattress.

‘Welcome home,’ I said.

The bedsit was the housing version of a pay and go sim card. Once you stopped topping up you ran out of minutes. In the first week of residence, the middle-aged man with a gold tooth was evicted for being late on the rent. Two men from the pub my landlord owned turned up and told him it was time to go. The evicted man was monument big. In the brief time of seeing him, he didn’t appear like the type of person who liked being told what to do. He had fists like cannonballs. I wasn’t there for his eviction. The other two men drank to his absence later that day. On my return from a random bed the following morning, shards of broken glass in the hallway glistened like stars at night. A bin bag covered a broken pane of glass on the front door. In the presence of these men, I felt as welcome as a typo on paper.

My landlord took cash in hand every Friday as payment. I made sure I wasn’t late. You had to go visit her at a pub she ran in a part of the city you only went to if looking for hard drugs or solicited women. Every time I entered her windowless, smoke-filled pub, there would be some beer bellied tattoo guy sat on a stool at the counter. Each week he asked me if I ‘needed anything.’ I was living off the rental grid due to a lack of income, good credit. I needed a lot of things, but politely declined. Bedsits were rooms rented to down and outs, nomad types. The rooms came without the usual legal obligations like a contract or deposit. Tax evaders, divorcees or opportunists often advertised bedsits on websites designed for the desperate. I had no income or abode and had just come off the road. Temporary rooms one could leave once finding something better—they gave me hope, I don’t know why.

The men I lived with were running away from something: debt, addiction, crime, themselves. Evening conversations overheard from the kitchen ranged from football losses to getting out on the piss. Between these men, there seemed little room in their lives for doing much else. I mostly kept to myself, while living among scarred and bloated men who were much older than myself. In my small windowless room I would read and write fiction or poetry. I did this in solitude at a time of having recently felt most alive in the world. Sometimes, I considered the men I lived among and what had gotten them to this place. If they—like myself, would ever escape the bedsit.

I read a lot of books at this time: Borges, Verlaine, Lorca, Fante, Moore, Baldwin, Lessing, Neruda, Munro, Baudelaire, Hesse, Yeats, Camus, Corso, Dickenson, Di Prima, Murakami. Reading distracted me from the reality life was not being lived as optimally as it had been weeks earlier in America. While backpacking, I had published my first poem in a now defunct literary magazine after countless rejections from editors and agents. I remember heading to a local magazine store to buy a copy of First Magazine on my return from America. I was so excited. The poem was published by an English teacher in Dorset. He told me there were 5,000 copies of the magazine in circulation—nationwide. I felt like the king of the little magazines. Near broke, living week to week among angry men in a bedsit you only lived in because you had to—I had made print.

Before moving into the bedsit there was great adventure. I had just returned to the UK from America enriched by cultural experiences spent backpacking overseas in a country full of immigrant stories, colours and accents and scents unlike my own. I had spent the previous weeks moving east to west, across the vast lands of Americana by bus or car or train or foot. At first, I had moved through a country where everything felt bigger, louder, overstated, alone with the vitality of an addict looking for a fix. I remember how direct and fast people spoke; the size of cars, meals and billboards compared to Europe. There was a feeling that people from all over really had come to find something more. I was one of those people. Foreign women.

Being twenty-two and alone in a new country, it was a little daunting at first. Back then, travel guides ruled smartphones. Instinct influenced decision making more than instant results via google. You had to go with your gut. Especially on public transport or when moving through cities at night—no google maps were available to lead you from wherever you’d ended up. 125th Street, Harlem, New York City, where the great jazz players once blew out in back-alley bars, chicken shops everywhere, a fat black woman with a beehive pushing a trolley full of bags telling me it’s time I went home. This first New York after midnight experience lives on somewhere inside of me, I don’t know why.

Soon enough, I found my feet on the road, where else would they be? And then I found other nomads and bohemians to travel with: creatives, students, workers. The creatives were often dirt poor and looked hungry. The students had graduated and were on a year out to find themselves. I found the phrase ‘year out’ conflicting. The workers were usually immigrants looking for something more than a time-consuming job or memory of a recent breakup. Cash rich time poor types. People who had made countless good decisions in life, only to end up unsatisfied with a rat race or career ladder. I also met opportunists who saw my foreignness and age as weakness. But it was the paperless immigrant from Mexico or Nicaragua or Russia or Albania; the one’s looking for work on a railroad or farm, a chance to learn English, clean—I wanted to spend time with. The one’s who were burning through the night on a bus towards LA or New York or the Badlands. Within the vacant eyes of these men and women was an urgent need to have something that could sustain them and their families.

*

Meeting people on the road who were unlike anything I had known before was a thrill. What I had read in books had entered my daily reality. As confidence grew, I began to meet people everywhere: on the street, in hostels, at cultural sites or in transit. The bonds I formed while in America were based on a longing for new experience. Finally, I was on the road the way I had read about in books—poor and hungry for more of everything.

Travel gives you confidence to approach strangers in a way growing up in the same place never could. America in my mid-twenties was an enlightening time of my life, one full of neon lights and midnight burn, all-night bars and counter-culture books that stirred the mind and opened my eyes to stories of other cultures. The landscapes over there were arresting. There are millions of lives being lived in thousands of ways. Whether sat on a train looking out at bison roaming the prairies or stood beneath the blinding neon lights of 42nd Street, overwhelmed by hustle. Out there, I quickly understood there are a million stories to be found in this world.

On the road, I found poetry in the streets as much as I did on any bookshelf. This helped fill a moleskin notebook with thoughts and ideas, random conversations. Moving across America, I felt freer than I knew what the word meant, in the bourgeoning years that had come before. The immigrant stories I discovered—in person or through stories, fuelled a desire to go further in my life. It was a time to let the candle burn. And I was hungry to meet people in search of something more than what they had been born into. And when I found these people, we would explore wherever we were together with an urgency that belongs only to youthful abandonment, a lack of having to be responsible.

*

Back then, I was young and boundless, excessive by nature and fuelled by a desire to read everything I could get my hands on about people who lived on the outside of society—whatever that means. Anyway, after weeks of travel, long rides on trains or greyhound bus, and a near mugging at a station by a couple of crazed street cats who smelt like rotten eggs; I arrived with a backpack in San Francisco. From downtown, I made my way onto a rickety tram that reminded me of Europe and headed for North Beach. The literary history of the area I’d read well about in books. Thirsty and overgrown, I checked in at a hostel named the Green Tortoise, took on some water, shared pot with a hippie in a communal area with picnic benches and a meditation room, slept for hours.

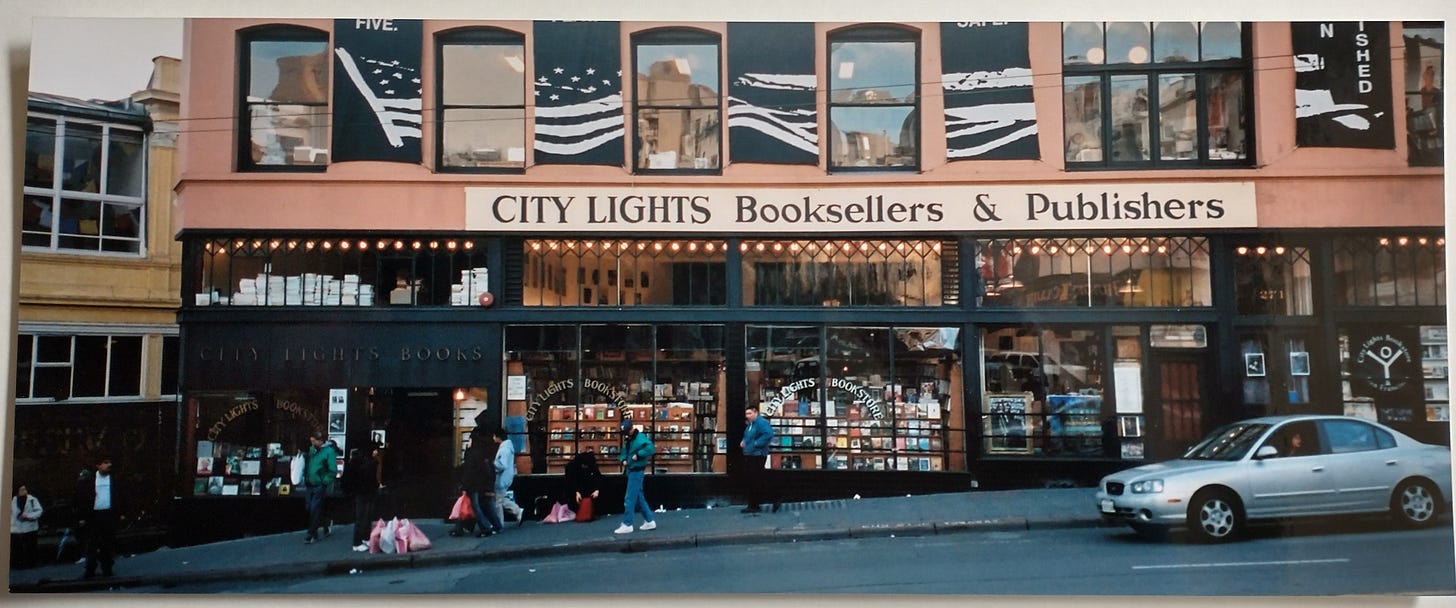

My final days in America would be spent sharing a dorm room with a painter who had worked farms all summer to fund their movement across America. There was a middle-aged man dressed in a hospital gown—and little else. And a dreadlocked hippie who loved Bob Marley and lived only to get high, man. On my first morning, as I made my way across the street towards City Lights Bookstore, a crazed local would inform me that San Fran was a 49-mile radius of madness. He also told me that whenever he stood up the sun shone, but when he sat down it would rain.

By day, I browsed the shelves of City Light Bookstore, bought what I could afford: Corso, Burroughs, Ginsberg, a few self-published pamphlets on a shelf left empty for tumbleweeds passing through to fill up with self-published poetry. It was a moving experience just to be in the store, let alone among books that would open my eyes to a new way of thinking, of feeling about a world far beyond my imagination. As a Beat Generation fan it’s hard to describe how sweet, rare and musty scented books, packed with words written by writers I’d admired since a boy, felt to hold in my hands as a young man.

At night, dizzy from words, I entered a bar next door named Vesuvio Café. In there, they played Miles Davis, Charlie Parker and Nina Simone. I knew all about the Beat Generation and the iconic names who had frequented both venues decades before—now I was drinking and reading as they had. Occupying these spaces, it changed who I was—it changed who I thought I could become.

Both venues drew an eclectic crowd: workers, tourists, hipsters, bookworms, pilgrims. Old beatniks sat cross legged on chairs scratching white beards or stroking strands of thin hair as they read in a corner of City Lights. And later, sat on wooden stools at the bar in Vesuvio’s with a Whiskey Sour or Old Fashioned to hand. Beneath a chandelier, between walls covered with known and unknown cultural icons. I took a beer and sat in a corner with a moleskin, wrote down what I saw unfold around me. I remember the colour green, trilby hats and suit jackets, murals and vintage décor that looked like they were from another time. I remember all of it like it was now.

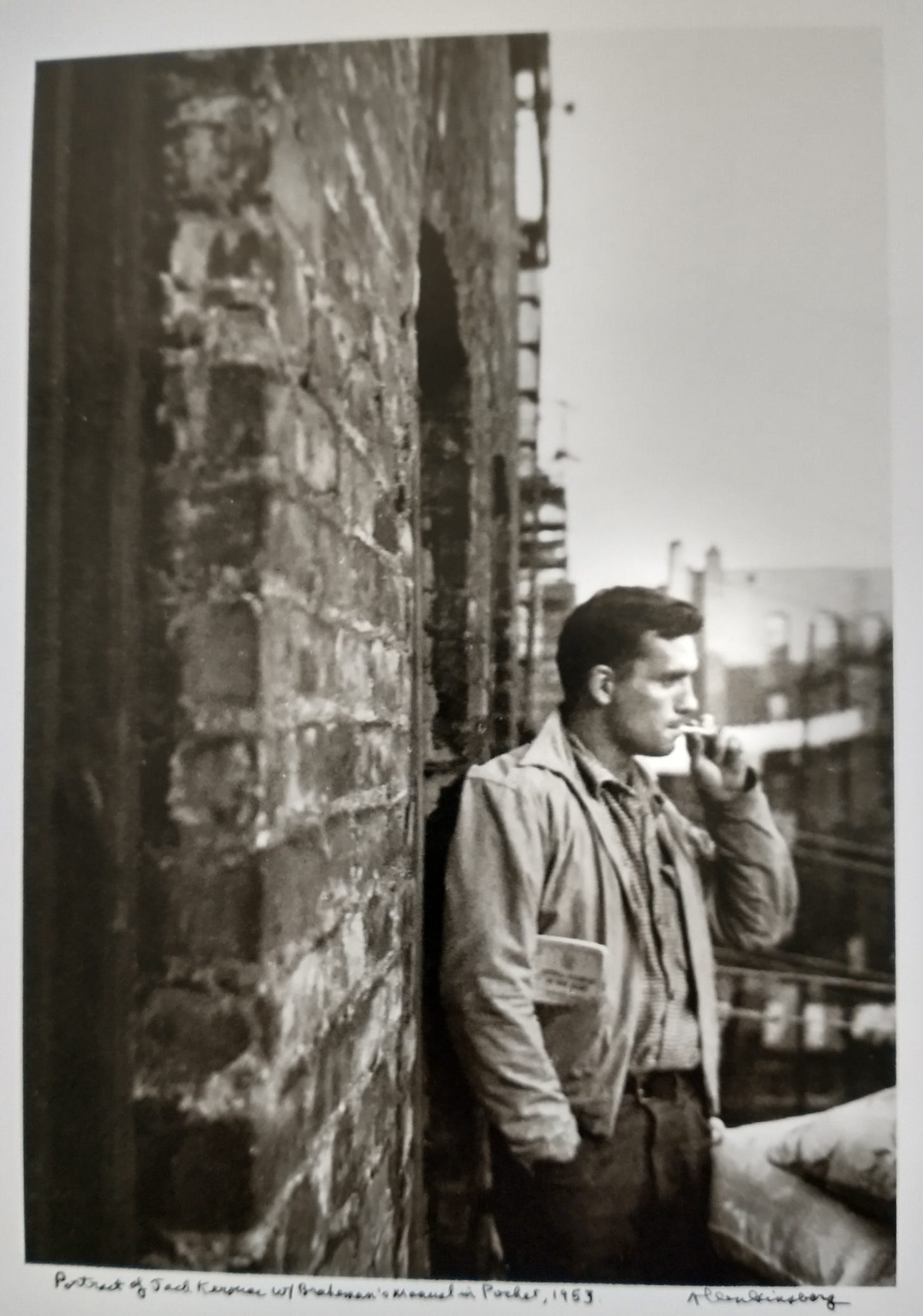

And as I think back on this time, away from my homeland once again, I can still smell the earthy must of paper, oak of wood and bourbon that wet lips after words of Di Prima, McClure, Kerouac. Corso’s hoodlum verse would guide me through the following days before a return to the UK and an environment I only wanted to escape.

City Lights Bookstore kick started a nomadic life that however unsettled it became; words were always present to centre me enough to go on. My time in San Francisco would end after a brief interaction.

Another pearler David! Great article. I'd love this to be part of a series so I could read more...

wonderful detail from beginning to end .